I've been thinking about the market lately. Not the local market where I buy fruit and vegetables, chat with the growers about conditions on the farm, see a few people I know, and maybe watch a busker.

|

| See you there Mr Bean! Source |

So many people seem enamoured with this amazing thing called the market and 'fixing the market' or 'finding a market solution' when we discuss numerous diverse aspects of our society - electricity supply, airline viability, water, aged-care, housing, finding a job.

But just what is the market? It seems big and ubiquitous, but strangely vague. It's obviously not a place, like my local market. So, what kind of thing is it?

And what makes the market the solution to all sort of pressing social and environmental issues?

Definitions and 'kinds of things'

These questions are challenging to explore, but they lead somewhere interesting. If you're tl:dr, you can skip to the recap near the end.

When I'm thinking about words, I start with the question: what 'kind of thing' is this?

A good definition starts with an 'is-a' statement (also is-an, is-the) that points to the 'kind of thing' that word represents - a dog is a (kind of) animal, fascism is a (kind of) system of government. The different 'kinds of things' are extensive, including object, action, location, state of being, process, collection, relationship, concept, etc.

I've underlined the 'kind of thing' indicated in the definition of the market:

♦️ a meeting together of people for the purpose of trade by private purchase and sale and usually not by auction

♦️ the people assembled at such a meeting

♦️ public place where a market is held, where provisions are sold at wholesale - a farmers' market

♦️ retail establishment usually of a specified kind - a fish market

♦️ rate or price offered for a commodity or security

♦️ geographic area of demand for commodities or services - sell in the southern market

♦️ category of potential buyers the youth market

♦️ course of commercial activity by which the exchange of commodities is effected: extent of demand - the market is dull

♦️ opportunity for selling - a good market for used cars

♦️ available supply of or potential demand for specified goods or services - the labor market

♦️ area of economic activity in which buyers and sellers come together and the forces of supply and demand affect prices - producing goods for market rather than for consumption.

Okaaaay. Each use of the word market is a different 'kind of thing': an action, a place, an area, a category, a price, a group of people, a concept, an amount of money, an industry. Each one makes sense separately, but in combination, they don't give me a sense of what 'kind of thing' the market is when politicians and economists tell me we need 'a market solution'.

And something this vague is supposed to provide solutions to social and environmental problems?

Reluctantly heading down the rabbit hole of word use in economics

So, I turned to a non-technical* definition from economics.

|

| A little trepidation Source |

The second meaning of the market is more helpful.

♦️ A market is the process by which the prices of goods and services are established.… Markets allow any tradeable item to be evaluated and priced... to convey information among economic entities… to regulate production and distribution.

Okay, this is getting somewhere. This disregards the participants, type of product, location, domain, type of activity, etc. of various markets, to clarify the 'kind of thing'.

The market is a process: a process of interacting to establish the price of tradeable items for resource allocation.

Most people would call the market a system, because of the complexities and multiple players. However, I'm trying to cut the complex concept of the market down to the bare bones to allow exploration. 'A process' is the most clarifying and fundamental concept I've found.

This concept sits below all the other uses of the word the market. Billions of people engaging in this process make up the market in the meaning of 'world economy'. Thousands of organisations impact, regulate, track, and speculate on the individual and aggregate process. It is so pervasive that we talk about the market as if it were a physical thing. In fact, we sometimes talk about it as if it were a person - 'the market reacted badly'; 'the market didn't like that news'.

But it's a process - a way of doing something.

The importance of process models of the market

|

| The water cycle process model Source |

Process model diagrams are designed to make the world easier to understand, to highlight the key components and relationships, and to help to develop new ideas.

It's not easy to create a good process model. If you simplify too much you leave out important aspects. If you put too much in, it will be too complicated to use. But simplification is necessary to study complex processes. They exist across most fields of study.

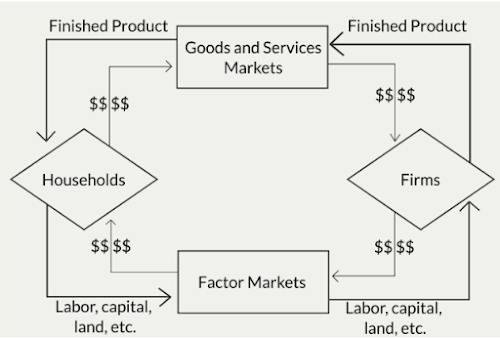

Economic process models describe the component parts of the market in boxes (people, goods, firms, money, etc.), the actions and relationships via arrows (producing, price, exchange, consuming, etc.) and all sorts of other technical concepts.

Here's one (of a number of options) process model of the market.

|

| A process model: the boxes and arrows show how the market works Source |

I don't intend to explore the process model itself; in fact, I won't be touching economic ideas at all.

Instead, I want to explore the underlying ideas required to create this diagram: simplifications related to what the world is and how it functions, how humans behave, and ideas about what to include and exclude in order to make a comprehensible diagram.

Economic process models of the market are based exclusively on people's ideas of how it works (theories). Economists 'test' these ideas using the simplified diagrams - the process model - and statistics. Until very recently, economists did not observe people in the market, or 'test' their ideas based on what actually happens in the real world (empirical research).

And that's economics: the study of simplified diagrams of how the market works to allocate resources.

Therefore, it is essential to understand how these process model diagrams of the market simplify the world in order to understand what 'market solutions' can offer us.

Simplification 1: The world is made up of 'things' - treated as 'tradeable items' in separated units.

Given it is a process 'to set a price for tradeable items', the market treats the world as a collection of separated individual units.

The market simplifies the world into 'things'.

This includes tangible products like apples, cars, diamonds, as well as non-tangible products like software, songs, DNA, a loan.

The market also treats services as 'things' (like hair cutting, training, plumbing, food delivery) by viewing them as 'tradeable items'. While the law differentiates between Products and Services and more recently Service as a product in terms of contracts and obligations, the market process itself treats them all as 'things' - separate items (e.g. visits, certificates, outputs, etc.) that can be tallied and analysed in terms of ideas like supply and demand.

|

| Supply and demand: P-price, Q-quantity of good, S-supply, D-demand Source |

It also treats abstract ideas - debt, insurance, risk, natural disaster probability, ideas, rental agreements, security and crime, etc., as 'things'. For example, debt is clearly not a material 'thing', but the market creates and trades in 'units of debt' (you'll probably have heard of the trade for 'collateralised debt obligations' that sparked the GFC). These tradeable 'things' stand in as a proxy for the abstract idea of debt itself.

Sure, we ALL know the world is not really made up of just 'things', but to be traded, to fit into the process of the market setting a price for e.g. debt, insurance, risk, ideas, etc. it has to be treated like it is a 'thing'. No one (even in economics) would say they ARE 'things', but their exchange is counted, tallied, averaged, used in algorithms, graphed, seasonally adjusted, etc. - actions you can only do if you treat everything as 'things'.

The market also treats the following as 'things': people's labour and needs, animals for human consumption and in the wild, social groups, expertise, quality, relationships, and environmental systems. For the market to set a price, anything complex is deconstructed into its component 'things'. So, a wilderness area is deconstructed into units of water, trees, large animals, etc.; a person's need for chemotherapy is deconstructed into the units of component materials and skilled labour needed to meet this need.

The very act of drawing a box around components in a process model involves treating them like 'things'. It's standard. In addition, the context of the 'thing' is not included. Context is removed to keep it simple so we can understand how the market works. It's common in all types of process models.

Anything that is not 'a tradeable item' is not relevant to the market, so it is outside its process model. Of course, economists are aware of there is a world outside 'the market'; they call them 'non-market elements'.

So, simplification number 1: the market process involving thinking of the world as a collection of 'things'; it involves 'thing-ifying' the world. It further simplifies these 'things' as individual units removed intact from their context.

(I'll continue to use 'things' in inverted commas when it refers to how the process model simplifies the world.)

Simplification 2: All 'things' have owners - ownership is transferred between buyers and sellers

Alongside the concept of the world as a collection of 'things', is the concept that every 'thing' can be owned.

Ownership is a complex concept, one we take for granted in Western cultures.

|

| Land enclosures and serfdom Source |

Property rights and rightful ownership is central to the market.

Property rights apply to physical things and land, but also all the non-tangible products, services and abstract ideas that the market treats as 'things' to trade. Large bureaucracies exist to administer and enforce patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain names and secret recipes so people can trade therapy treatments, music, theatre, research, software code, business reach, food franchises, etc., on the market. They establish the ownership of the 'tradeable item', with the law used to stop ownership infringements. The market requires that ownership exist and is enforced so that creators and providers can make money through the market - by setting a price through trade of what they own.

The process model for the market simplifies the concept of people to either buyer or seller. You either own the 'thing' or you don't - the market simplifies interaction and relationships into the transfer of ownership. To avoid too much complexity in the process model, other types of relationships are not included.

|

| Ownership transfer we understand Source |

(That's why it is impossible to have a market economy without a government to enforce property rights. In fact, once you realise how central the exchange of 'ownership of things' is to the market, you realise that the idea of a 'free market' without government intervention requires (at least) a willful blindness.)

So, simplification number 2: the market is a process of setting a price for the exchange of 'the ownership of things' between sellers/producers and buyers/consumers.

Simplification 3: Every 'thing' has a price established through exchange between buyer and seller - value equals usefulness equals price (often) equals importance

One often mentioned defining feature of the market is the use of price to convey information between people - a 'price signal'.

In the process of exchange in the market, the ownership of every 'thing' is assigned a price.

From the perspective of the market, the price is the only measure of its value. It's not that economists think nothing else matters, or don't personally value their children (for example), they just assume that the price for a 'thing' encompasses all the other ways that humans understand 'value'.

|

| Human 'values' plastic rubbish at $15k |

What the price reflects, and whether the 'price' is a full expression of 'cost' is still fiercely debated 500 years after the market was born. Keeps the economists off the streets at least. But 'price' is THE arbiter of value.

In contemporary economics, utility - the usefulness of something to the buyer - is the dominant idea about how humans assign value to a 'thing'.

From this standpoint, the market treats land, water, air, trees, work, even money itself, as 'things' with a value based on how useful they are to humans. Their usefulness is reflected in their price, or how much buyers will pay to own that 'thing' for their use.

So, the process model simplifies how humans value 'things' to: value equals usefulness equals price.

But outside the market, you and I more often use value to mean importance, particularly personal importance. When I say that something has value, it often has little to do with its price, but something else about it - for example, my grandmother's vase has value for me because she gave it to me; the river has value for me because I relish feeling relaxed sitting beside it. (I reckon at least a million other articles exists in sociology, philosophy and religion about 'a theory of value' - I haven't read them all either!)

|

| Source AZ Quotes |

This leads to a common word meaning slip: in the market process model value starts out as equal to usefulness which equals price, but in its application, this often slips to equal importance. I'll explain with an example.

I'm sure economists would agree with most people that 'you can't put a price on human life', but the market, um … puts a price on life.

|

| Source SMBC |

The market simplifies humans and human needs to their price or cost value, like the cost of health services, the cost of crime, the price of aged care, the price of entertainment, the cost of education, etc. Economists calculate cost/price using lots of averaging (e.g. across demographics), prediction (e.g. about life span) and subjective opinion (e.g. about what makes a good life), so humans and human needs can be considered in the process models related to health economics.

However it is done, the market process model requires that people's lives are 'thingified' down to a single number representing a price value, e.g. the Value of a Statistical Life Year (VSLY), the Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY).

No doubt, the many fans of the market agree that other things about humans are important. But the market itself - the process of setting a price through exchange - can't integrate our personal and varying ways of valuing people. These defy the simplification required to be included in the market process model.

|

| Shock will always get you in the news |

It's a slip of the meaning of value, but it happens a lot in the market. We saw some people using this slip in meaning when they argued to allow elderly people to die of coronavirus - the cost of keeping them alive was higher than their potential production value. That argument is logical only if you see the world in the way the market simplifies it. (Check out this brilliant cartoon by John Kudelka on that point, which I can't reproduce as I don't 'own' it.)

We are shocked when price is used to equal importance referring to people, but the market process model requires this thinking about everything in the world. In fact, economists try to put a price equivalence on all the other ways humans understand value, particularly about the natural environment.

So, simplification number 3: the market defines value as the usefulness to buyers, usefulness is represented in the price established through exchange, and in application price slips to equal to importance.

Recap: what is the market?

I started with a quest to clarify 'kind of thing': the market is a process.

The market is a process of interacting to establish the price of tradeable items for resource allocation. (The aggregation of gazillions of these interactions is also referred to as the market, meaning the global capitalism world economy.)

Economists rely on process models (simplified diagrams) to understand how the market works. Various process models all rely on three key simplifications:

♦️ the world is made up of separate context-free 'things' (or proxies)

♦️ every 'thing' can be owned, and interactions between people are for the transfer of ownership

♦️ price represents the value or the utility of the 'thing'.

That's certainly not how I see the world.

I don't see the air or a river as 'things' to be 'owned' with a 'price' based on their 'utility'. I don't see people in any sense to be valued by their price/cost.

I can see that the market simplifications about the world can be useful when we are thinking about tangible things (like apples) and services (like plumbing), but I see all sorts of issues with extending these simplifications to everything about the world, especially people. We've recently lived through the effects of treating abstract concepts (like debt) as tradeable items. I don't want to live in a world where relationships are reduced to buyer or seller. And surely, none of us wants to go back to a time when men owned women and slaves.Beyond these unpalatable simplifications, the process model of the market excludes context and many aspects of the world (i.e. non-market elements) that would seem essential to understanding how the world works, like the social nature of humans.

In fact, it seems to me the process model for the market simplifies the world so much that it does not reflect reality at all.

It's a worry that economists base all their theories on these simplifications.

So, if that's the market, what would a 'market solution' look like?

It's a worry too if these simplifications are the basis of market solutions.

The market has advantages and disadvantages, just like other processes of allocating resources among people (reciprocity, redistribution, commons). Economists tell us it is much more efficient and effective than the other processes, and point to the growth in global wealth since the market was created.

The three key simplifications of the market seem reasonable if the problem is how to get food from producer (efficiently) to those who need it to eat (affordably, sufficiently.)

But... I'm no closer to understanding what 'market solutions' can offer more broadly. I don't understand how 'a process for setting a price through exchange' can solve our pressing social and environmental problems - like poor quality aged care services, inadequate health services, impending climate change disaster, questionable standards of education from school through to tertiary levels, lack of water flows for dying wetlands, and staving off mass extinctions.

I cannot think about those problems in terms of 'things', 'ownership' and 'price'. But those simplifications and that kind of thinking would surely underpin a 'market solution' given it is based on the market.We know from other areas of study that we need to understand and clearly define a problem in great detail before we can attempt to solve it. We then match solutions to the problem. However, it seems though that the market offers one type of solution only. There must be more to it.

I will continue my exploration in part 2 where the market process model somehow gets a life of its own.

Before then, I'm going to talk to the apple man at the local market about making our transfer of ownership of 'things' more efficient.

Footnotes

* I used non-economic sources for information about these concepts, as economic writing assumes you already accept its view of the world, and I didn't want to start from that assumption.

Credits for images, used under Creative Commons Licences

- Mr Bean: https://memegenerator.net/instance/64952445/mr-bean-its-market-day-if-you-know-what-i-mean

- Down the rabbit hole: https://eleenakorban.wordpress.com/2010/06/06/down-the-rabbit-hole-we-go/ [CC BY-SA]

- Process model for the watercycle: Anishct https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7c/HydrologicalCycle1.png [Public domain]

- The circular flow model: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circular_flow_of_income#/media/File:The_competitive_price_system_adapted_from_Samuelson,_1961.jpg [Public domain]

- Graph of supply and demand Paweł Zdziarski, Astarot : https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7a/Supply-and-demand.svg [CC BY-SA]

- Land enclosure: The land magazine UK https://www.thelandmagazine.org.uk/articles/short-history-enclosure-britain [Not specified]

- Ownership exchange: https://technofaq.org/posts/2018/06/should-i-buy-a-car-with-cash-or-a-loan/ [CC BY-SA-NC]

- Ooshie value: snipped from the socials

- Oscar Wilde quote: AZ Quotes, reproduced according to site permissions

- Economics 101: Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, no information provided regarding reproduction

- Tony Abbott: snipped from the socials

- All other images by the author

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated. After you click Publish (bottom left), you will get a pop up for approval. You may also get a Blogger request to confirm your name to be displayed with your comment. I aim to reply within two days.