This post builds on the ideas explored in the previous Post truth posts: part 1 - a false metaphor, part 2 - a metaphor that fits, part 3 - reviewing the project brief and part 4 - tell me a story.

In part 4, I described how the walls of the metaphoric house of truth are constructed. The metaphoric walls represent our interwoven explanatory stories, shared and reinforced by lots of people throughout life. Our explanatory stories run constantly under our thinking, most often without our awareness. It's hard for us to pull out any single 'story', think critically about our understanding of the world, or notice if some stories have only a tenuous link to 'facts' about reality (the metaphorical floor).But we don't really want to anyway; why take a wrecking ball to the walls of our own house? We like living there!

In the last post, I suggested that our shared explanatory stories meet fundamental human needs in a way that facts cannot. Those needs include our need to understand 'cause and effect' so we can do things, out need to belong and share a sense of reality with others, and our need to feel safe.

Here's an idea: truth is the status that we give to the explanatory stories that meet these human needs.

'Whoa!?!' you say. 'Don't facts count for anything? Doesn't being right or accurate matter? Can I just call any random idea truth if it 'feels' good then?'

Very important questions. To begin to answer them, in this post I'm looking into the nature of our relationship to truth, how truth meets fundamental human needs.

I want to explore how truth makes us feel.

The need to understand what causes things to happen

Humans have a fundamental psychological need to makes sense of the world, to understand why things are the way they are.

We think about the world as functioning according to certain 'laws' (physical or religious), as following patterns that we can determine. We make sense of the world most readily through 'explanatory stories' that spell out 'if you do this, that will happen'; 'if this happens, then that will follow'; 'this happens because that makes it happen', etc.We constantly look to identify 'causality' - which actions cause what effects. In fact, some developmental psychologists think that determining causality is a human drive, like hunger and sex.

In evolutionary terms, identifying and sharing ideas about causality through explanatory stories about the world and about people would have been important for survival. Knowing that, for example, if you eat rotten food, then you will get sick; if you don't share food today, then no one will share food with you tomorrow; the mudslide happened because it had rained so much, etc., guides what you do and how you act with other people.

From the age of about 2 and throughout our lives, we think about almost everything in the world in terms of cause and effect: a causes b, without necessarily being aware of it.

|

| Source |

It gives us a sense of running our own life, of some degree of control over what happens.

We use it all the time: If I work hard at school and get good grades, then I will get a well-paying job that I enjoy. If I want the laws on sexual assault the change, then I can protest and write to politicians. If I don't want to get fat, then I should avoid eating the whole packet of hot-cross buns (because that will make me put on weight). I'm poor because the bosses are greedy, so they won't pay properly. I can't get a job because China.

Identifying causality makes sense of the world and provides the sense of certainty we seek all the time. It also allows us to apportion responsibility and blame to other people: who caused this to happen?

The identification of causality becomes an explanatory story we share with our families and community.

We do it all the time, but that's not to say that we identify causality accurately.

We need to understand causality, but we like it simple

We might think of the explanatory stories of ancient humans, like thunder being caused by an angry god, as simple, ignorant ways to make sense of a complex world they didn't really understand.

Well, despite massive scientific advances, most of us, most of the time, continue to rely on simple, poorly-formed ideas to make sense of a complex world we don't really understand.

Because, while humans have a drive to understand causality, we also have a strong preference for simple causal explanations. We hate contradiction, and we don't like to think about complexity.

Humans cannot hold two contradictory ideas with any ease - we experience what is called cognitive dissonance. It feels really bad. We take steps to remove the contradiction between what we expect (our explanatory story) and what we see (what we experience). If necessary, we just ignore what we see with our own eyes! We need to relieve the bad feeling.Scientists studying complexity avoid using a causes b reasoning - because that's not how the physical (or social) world actually functions. They have developed alternative ways to think about causality, but humans are just not very good them.

We might agree that 'in theory' the world is very complex, but when we need to make sense of the world, or make a decision about what to do or who to blame, we resort to thinking in terms of a causes b.

For example, a well-known image from complexity theory, the butterfly effect (explained here), is often misinterpreted to mean that a butterfly wing flap can cause (through a chain of a causes b causes c causes d causes e, etc.) a hurricane (an effect). It is telling that the area of science that warns against relying on simple a causes b thinking gets understood through a causes b thinking!

When it's too complex to fully grasp, that feels bad too.

|

| Source |

We also prefer simple explanations for why other people disagree with our understanding of the world. We can't abide contradiction or complexity, so we have to dismiss contrary views, and we do this most often by dismissing the person.²

They must be stupid. Illogical. Irrational.

Illogical and irrational

Well… sorry to be rude, that's not wrong.

Ironically, despite how central it is to our functioning in the world, we are really, really bad at determining causality. We not only lean to simplistic explanations, we are often entirely illogical and irrational.

For example, humans frequently develop the idea there is a causal connection between two completely unrelated events. We might see causality based on coincidences or something happening soon after: I took a vitamin pill. Soon, my aching tooth felt better. The vitamin pill caused me to feel better.

Humans' poor reasoning about causality is shown by this list of several hundred thinking biases - common and well-known ways that we are illogical or irrational. Examples include our tendency to believe statements if they are repeated (regardless of veracity), to believe authority figures (regardless of their knowledge), to draw different conclusions depending on how an argument is presented,

Most of us (including those who research thinking biases), most of the time, don't tend to realise when our reasoning is biased or illogical.

|

| From a brilliant cartoon from The Oatmeal. |

So, now I can say - we all need to render the world understandable and predictable so we can feel a sense of certainty, and whichever explanatory stories achieve this is what we call truth.

And that's the kicker: even though we have a simplistic or inaccurate understanding of causality, we are deeply attached to our explanatory stories. They provide a feeling of safety and being in control of our lives. We will defend them against any challenges, sometimes with deadly weapon.

The Oatmeal says it well: We carry our beliefs about truth around 'like precious gems wrapped in hand grenades'.

No need for accuracy to feel certain

It's hard to convince anyone (or accept yourself) just how poorly we reason about causality, how wonky our understanding of the world might be, how strange our explanations might appear to others.

Instead, our need to understand why things happen manifests as a conviction that our explanatory stories are right, and we give our understanding of the world the status of truth.

If we see 'facts' that contradict our world view, we don't tend to look at our explanatory stories and wonder if we are right. We are much more likely to resort to one of hundreds of thinking biases to shore them up and make them even stronger.

For example, if our 'just world' explanatory story doesn't seem to be holding up (We worked hard, we're kind to people, so we are supposed to now have a comfortable life, but we don't), then we look for an explanation that allows us to maintain our attachment to our 'just world' story and identifies the cause of it failing on this occasion (e.g. someone is causing a problem deliberately, someone nasty is trying to control us). Likewise, we can very easily disregard 'facts' or our personal experiences that conflict with the explanatory stories of our community's politics or religion.

Conspiracy theories, e.g. QAnon, might seem irrational to outsiders, but they meet this basic human need to reinforce one's sense of truth (wall of explanatory stories), they provide simple reasons for 'why things suck' in the form of a causes b, they remove contradiction and complexity, they render an often unpleasant and scary world as understandable and predictable, and they show what you what is under your control and what you can do (e.g. storm the Capitol building).

But it's not just conspiracy theorists. All humans³ tend to distort logical thinking through confirmation bias - searching for and interpreting evidence that supports what we already believe - and its evil cousin, the backfire effect - where contrary evidence only results in you strengthening your conviction.

Our sense of truth allows us to avoid confusion and the discomfort of 'Hmmm?'. So, we use biased thinking and poor logic (subconsciously, of course) to protect and preserve it against any challenges.It's strange: identifying causality is vital for humans, yet it doesn't have to be accurate.

It should matter more, shouldn't it, if being accurate about reality and truth was critical for survival? And yet it doesn't.

Sharing the truth around

The most important factor for human survival is belonging to a community: our human relationships and social status.Belonging to a community is based upon sharing a sense of reality, of how the world is. An individual who doesn't is considered psychotic, described as having a 'loss of reality', a very scary experience. A shared sense of reality, and therefore of truth, is the basis of a shared social systems of behaviour and roles.

|

| From Wait but Why? All your 'why's answered on one site! |

It is the shared status of the explanatory stories in our family, society, local community, church, or cult, gang, political party that matters most, more than their accuracy.

So, don't facts count at all?

This might all sound a bit concerning; like humanity is on the wrong path to truth.So, if explanatory stories don't have to be factual or accurate to become integrated into people's sense of truth, can you just make up a new story today and call it truth?

Well, no. Or, only occasionally; only if you can convince enough people to share your new truth. History tells us this happens from time to time. For example, the 74 million Americans who voted for Trump in 2020 accepted his fact-free explanatory stories for why their lives suck and who to blame for it - enough people to provide mutual reinforcement for this 'truth' in a community of believers. The rest of us looked on, and wrote alarmed articles about fake news and post truth which had no effect at all.

Don't facts count at all? Is the alternative to the journey metaphor's single, objective, external truth an image of humanity living in a metaphoric house constructed of delusions?

Well, again, no. Agreeing and disagreeing about truth still involve facts and thinking logically for most of us.

You can't just make up your own truth. This brings us to what (usually) stops that happening.

Building codes and building inspectors

I've talked so far about the process of the social agreement for truth, the metaphoric house construction process.

But there's a more fundamental, probably more important, agreement. Over the centuries, humans have also spent a lot of time and energy reaching agreement about the best method to agree on reality and truth. (In short, an agreement on the rules about how to reach agreement.)In the house construction metaphor for truth, think of it as the building code. Just as a building code guides the construction of a physical house, a building code exists for constructing truth. There are rules and guidelines. There are processes and there are taboos. They can change over time. And there are those who place themselves in the role of building inspector from time to time.

Facts still matter - that is one of the rules of contemporary western society in constructing truth. How this works is the topic of the next post.

It is what it is…

We each hold a strong sense of truth; we all reside within a house of truth constructed and shared by our community. It works, it lasts, it provides shelter and safety.

However, we tend to reject the idea that our explanatory stories are just our way of making meaning of a complex world. Instead, we think our world view is how the world is. It feels right. We feel certain that we know truth - objective, absolute truth.

But if someone asks us how it was built, how we know truth, we struggle to explain. Truth just is. The social construction process is invisible to us. Our biased reasoning to maintain what we hold as truth is also invisible to us.It's like a joke we play on ourselves: explanatory stories form our sense of truth, but they don't have to align with reality, they don't have to be 'right'. We have a drive to know causality, but we're rubbish at everyday reasoning about it. We consider the agreement constructed by our community as objective truth.

I'm not suggesting that humans need to be different, that truth is a matter of better logic or better self-awareness.

What we need to do is acknowledge what it is.

At the moment, we are staring into the distance at what we want to find: objective and absolute truth must surely be out there, we'll find it one day at the end of our journey. We still think of truth in the terms of an outdated religious metaphor.

If we looked closer to home, at the floors and walls of our socially constructed house of truth, we could start to see the human relationship with truth as it is.

What we hold as truth is the understanding of reality constructed through our relationship with many people, that meets our deep human need to see the world as meaningful and logical and coherent, that which relieves or provides solace for our many 'Hmmm?' moments with a satisfying or comforting 'Ah-ha!' moments.

Truth is the status that we give to the explanatory stories that meet our need to makes sense of the world, to belong and to feel safe.

Footnotes

- Agents are goal-directed entities that are able to monitor their environment to select and perform efficient means-ends actions that are available in a given situation to achieve an intended goal. While the sense of agency refers to the sense of control and sometimes to self-efficacy, which is a learnt belief of an individual about his or her own ability to succeed in specific situations.

- For example, when a politician we think inappropriate (like Boris Johnson) gets elected, we reach for simple explanations to dismiss this outcome - voters are dumb and gullible and they got tricked by a conman. Or people are just racist and nasty. Not something complex about human need for stories that comfort and make them feel better about their shitty lives and show them who to blame. Not something complex about backroom maneuvering to maintain the neo-liberal grip on the economy through promoting buffoons who are easier to control and dispose of puppets. Not something complex about nostalgia and the tendency of people to believe in symbols and abstract concepts like 'nationalism' and patriotism manipulated by a media mogul who stands to make more profit from social discord.

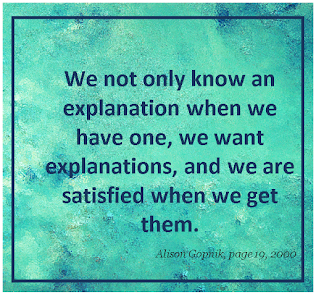

- An example of my own biased thinking: I know there is a tonne written on the concept of a drive for causality, but I know I agree with Alison Gopnik's ideas, so I've picked her 2000 article to guide my writing. She says:

- humans are designed by evolution to construct 'causal maps' - abstract, coherent, defeasible representation of the causal structure of the world around us,

- humans evolutionary advantage stems from our ability to adapt our behaviour to a very wide variety of environments. In turn, this depends on our ability to learn swiftly and efficiently about the particular physical and social environment we grow up in; uncovering 'causes' is the central feature

- children as young as 3 'organise the world in terms of underlying causal powers of objects and to seek explanation of new causal relations'

- the assumption that there is some underlying causal structure to be discovered remains constant across domains [of child development]

- we see both extensive causal exploration and even some more systematic experimentation in children's spontaneous play

- Getting a veridical [accurate] causal map of the world allows for a wide range of accurate and non-obvious predictions, and these accurate predictions, in turn, allow one to accomplish other types of goals that are more directly related to survival

- we not only know an explanation when we have one, we want explanations, and we are satisfied when we get them.

- If by accurate, we mean the dictionary definition of truth: the condition of a belief or idea being in accord with fact or reality, humans hold innumerable inaccurate ideas they think of as truth. Here's a tiny sample of mostly innocuous inaccurate ideas; I'm not going into religion or ideology!

- Reading in dim light will cause sight problems ruin your eyes

- The colour red causes bulls to get angry

- You are the result of the fastest sperm to get to the egg in your mother's uterus

- Pressing the 'door close' button in elevators causes the doors to shut

- An electric current is the flow of electrons through empty wires, like water would

- The diphtheria vaccine causes SIDS

- Humans are descended from monkeys

- Breakfast is most important meal of the day

- The government controls the economy, and economics can make reliable forecasts

- Expensive art is the best, because the high price reflects its outstanding quality

- Our brain is like a computer

- Mental illness causes violence.

Images, used under Creative Commons Licences where provided

- Wrecking ball: Rhys Asplundh https://www.flickr.com/photos/rhysasplundh/5202454842/ [CC BY]

- Gopnik quotes 1 and 2: created by the author from text from Explanation as Orgasm and the Drive for Causal Understanding

- Job gone to China: http://www.quickmeme.com/meme/3ul39n [Used under terms]

- Ignoring the facts: snipped from social media, no source provided

- Wrong and stupid: https://imgflip.com/memetemplate/182937679/Youre-not-just-wrong-your-stupid [Used under terms]

- Gems in hand grenades: a frame from a long but brilliant cartoon by The Oatmeal on confirmation bias and the backfire effect, which you really must check out. [Fair dealing]

- Auden quote: created by the author from the book review by Brain Pickings

- Overstory text: created by the author from text from the 2018 novel by Richard Powers. In the novel, a character is reading a book called The Ape Inside Us by a Professor R.M. Rabinowski. While this book and author is fictional, it is based on a real book called The Ape Within Us (1978) by John Ramsay MacKinnon which explores this topic. Read more

- Other people: a frame from the always entertaining Wait by Why https://waitbutwhy.com/2014/02/pick-life-partner.html [Fair dealing]

- Street signs: https://24hdansuneredaction.com/en/presse/08-the-truths/ [CC BY-NC-ND]

- Rules: Nick Youngson https://www.thebluediamondgallery.com/tablet-dictionary/r/rules.html [CC BY-SA]

- Overstory text: created by the author from the 2018 novel by Richard Powers

![gopnik quote 1 The assumption that there is some underlying causal structure to be discovered remains constant across domains (of child development] Alison Gopnick, page 12 2000](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEifBDZIHDP3ylDqC5-tuEbyrcqB_yN3poXCfJEPkGf46Je7bAwu2aa5a2SLlAja_4nciB5UAFH4BDPKl0_6QpzmnmS3z415QN7ZAWadrmYFTnTXocCTLBeLeiTtAe5I2UvsWvdWB-3CdMS9/w317-h296/gopnik+quote+1+-+Copy.PNG)

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated. After you click Publish (bottom left), you will get a pop up for approval. You may also get a Blogger request to confirm your name to be displayed with your comment. I aim to reply within two days.