Do you suffer from FOBA: a fear of being average?

FOBA, sometimes FOBO (fear of being ordinary), seems to be pretty common (here, here, here and here). If you suffer from a fear of being average at least some of the time, then you probably are … um… average.When I read the word average in articles about FOBA, I see several other meanings lurking behind it.

To me, fear of being average appears to be a modern condition caused not by illness or injustice, but by sloppy word use. Sloppy enough to cover a fear of something else entirely.

In this post, I focus on average when it is used and misused to mean normal, and in part 2 I'm going to explore average used to mean boring.

Why we can't all be 'average' or 'normal'

First, a brief review of the concept of average (or 'mean') from statistics¹. (Don't skip it because you don't like stats; there's none of it here!)

|

| While no individual is 145.8 cm tall, this single number (average, or mean) represents the height of the group. |

♦️ a single number that represents the general significance of a set of differing numbers in a group.

This representative single number is useful for comparing groups or tracking change within a group over time. Averages can be misused and misleading, but that's not my focus here.

I want to focus on the concept of an average. Four things are important:

- you can only generate an average using measurements (you can't generate an average of discrete items like events, things or categories)¹;

- you need to find a suitable single measurement to represent what you are interested in - height, aggression, job satisfaction, reading ability, quality of life, etc. (this is trickier to do than it sounds);

- you consider that a calculated single number (the average) can usefully represent the whole group (you wouldn't use an average of the ages of mum, dad and three young kids to represent a family's age; what would that be useful for?);

- you need a range of differing measurements for an average to be a meaningful idea (you don't talk about the average width of washing machines because they are all one of two standard widths).

The final point is critical to understanding the meaning of the word average: it requires and implies a spread or range of measurements.

|

| The normal distribution curve; one of many possible distribution curves |

The 'normal distribution' is the most important distribution in statistics because many natural phenomena (such as blood pressure, machined parts, human height, error in measurement, sizes of snowflakes, lifespans of light bulbs, test scores, milk production in cows, etc.) display this shape when measured, analysed and graphed.

But it's only one of many possible distributions.

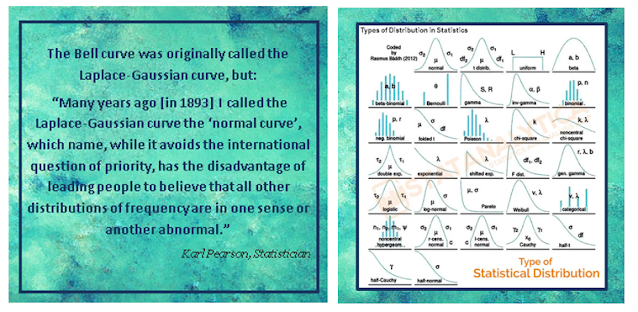

Distributions of measurements can take lots of shapes (with great names like Poisson, Cauchy, and Weibull), all of which are 'good' and 'normally seen' in statistics. The Bell curve was originally called the Laplace-Gaussian curve, but changed due to politics in the mathematical world. Yes, even maths has politics!

So, normal is jargon from statistics that refers to the shape of this graph. It doesn't mean good or correct. It describes one possible spread or distribution of measurements in relation to an average.

And yes, normal is not a great name really. It creates real problems in how stats is understood.

The 'normal curve' does not imply that people who score around the average are normal. The meaning is quite different from our everyday meaning of normal: 'usual, ordinary, not strange, not abnormal'. Normal refers to this particular pattern of distribution, not any specific measurements.

Statistically speaking then, we can't all be average, and no individual can be normal. And average does not mean the same as normal. That's the takeaway.

If we can't all be average, why are so many people afraid they might be?

I think it's because these words slip into everyday use to equal each other, and they take on other meanings entirely.

When average does mean normal

Recapping: the average - the midpoint, and normal - the distribution pattern, are two quite distinct concepts in statistics. Average¹ can only be used in limited situations for deciding if an individual is normal in the sense of 'not abnormal'.

Medicine, for example uses the concept of average to mean normal, in contrast with abnormal. It does so with very carefully constructed 'normed' tests² - which allow specialists to compare an individual's result to both the average and the normal distribution curve for the whole population. If some measure e.g. bone length or lung capacity, is outside the average range, this indicates the doctor should intervene or treat the illness or condition.Average on such tests means normal: within a range considered safe, healthy or desirable. If we have a medical test, we like our results to be average, normal, typical.

Other examples when average equals normal include, 'The east coast had normal rainfall for the summer. Covid has impacted the country's normal death rate.

The ubiquity of such examples is perhaps the reason that average is very often misused to mean normal when it shouldn't be.

When average means most common, and normal is the wrong idea

Normed tests² of learning and skills are also sometimes used in child development and education.

We expect a lot of variety and individuality in children's development and learning, particularly up to 8 years old, and this is shown by the wide curve and long 'tails' of 'normal distribution' of measures of reading age, concentration span, time balancing on one leg, maths knowledge, etc.

Average on such tests means most commonly seen, most frequently observed at this age.

A score (e.g. on a reading test) at some distance from the average point is less common, it occurs less frequently. Alone³, such a test result says nothing about whether a child's development is normal. A more important measure is progress in learning over time.

But way too often, this expected variety in speed and path of development is contrasted negatively against the single figure of the average: 'Your child scored right on average, she is normal'; 'She scored below the average, she is not developing normally.'

One of my children failed many of her child development tests at various ages. For example, she was well below average in knowing her letters; she was put in remedial reading in Year 1. But I thought she was okay⁴ and that one score wasn't the whole picture. And, without any extra help, by about 8 years of age was doing well at school.

My child's early development was normal (not abnormal), but not average. She did not follow the most commonly seen, most frequent path to normal development. For me, that wasn't too problematic; but parents without knowledge of the expected variation in child development might have found the test results quite distressing.

When misused in child development and education, an average can become like a tyrant, with expectations that learning, skills and abilities must conform to a single number - age of walking, reading age, number of books read, mathematical ability, ability to skip, etc.However, it is not reasonable to expect all children to achieve the average in their learning. This wrongly suggests that in an area in which we expect a lot of variation and uneven patterns of development, that average is the only normal. It can cause considerable distress in parents of young children.

This meaning starts from the statistical concept of average being the most frequently seen (most people at that point), but flips to most frequent to equal normal and infrequent to equal abnormal. Neither of which is necessarily true. It depends on what is being measured.

There are many aspects of human development and experience that can be considered normal (not abnormal) even when test scores don't touch the average (most common). Using average alone, we can't say that just because a learning path, ability or behaviour is rare or less frequently seen, that is it ‘abnormal’.

Average and normal meaning mediocre

The flip side to average scores being wrongly equated with normal in some areas of life, is when average scores are unsatisfactory.

We colloquially use average to mean mediocre or even substandard: 'The service at the restaurant was average'; 'The singer had a very average voice.' It's a subjective judgment of quality. Not terrible, just mediocre. We expected excellence and we got average or below our high standard.

Expectations play a big role in the use of average to mean mediocre or not satisfactory in child development and education as well. Some parents expect their child to achieve better than average on all sorts of measures. They like to think their child is special. The paper 'My child is god's gift to humanity'⁵ showed that parents' ratings of their child's smartness (IQ) was consistently higher than how smart the child actually was.The study found those parents who believe themselves to be superior to others are particularly inclined to overestimate their child's ability, perhaps an extension of their own 'excellence'.

Such parents hassle teachers to cater to their 'gifted' child and push their kids to do way better than average. Average is not good enough. That's a bit tough for everyone given what we know about average and the 'normal distribution' of learning and abilities.

Average in this case means mediocre, and no parents wants to think their child is just so-so.

No one thinks they are just average

Interestingly, we all tend to think that we are better than average on all sorts of things.

For example, 93% of drivers think that they are better than average at driving. And yet, how could this be? The concept of average requires a spread of measures of whatever ability is being measured. 49% of the population must be 'below average'.

We don't think we are average because many of us overrate ourselves a lot of the time.The famous Dunning-Kruger effect shows that we are often pretty woeful at assessing our own abilities. Those without much ability don't realise it, don't know enough to know what being 'way above average' entails, and can't accurately rate themselves.

If we care about something (e.g. our work, our parenting, our artistic efforts, our athletic skills), we don't like to think that we are not good at it. But it's likely that we are either average or below average on lots of things we do - that's what a 'normal distribution' requires!

We've overlaid average or below average with a judgement of being substandard because we like to think we are special too.

When average slides to normal as a moral judgement

But something even more concerning happens when we talk about people's behaviour, preferences and attributes.

Sometimes, when we use average to equal normal, average jumps from a numerical concept to a moral one.

Too easily, the statistical average can become a proxy for what ought to happen and a value judgement of those who are not average.

If you read that the average number of books read by children is 2 books per day, then you might judge the parents of children who don't as lazy or negligent. If a magazine tells women that the average number of sexual partners before 'settling down' is 3, then you might think any woman who has 20 partners is immoral. If the OECD reports the average time to be unemployed is 10.7 months, then newspapers might spin this as anyone unemployed longer than this must be a dole bludger. Given the average number of children in a family in Australia is 1.8, you might think someone with 6 children is irresponsible. If you know the average price for takeaway coffee is $3.35, you might think your local shop charging $4.00 a cup is ripping people off. If you have heard that the average time to reach ejaculation is about 5 minutes, you might consider any man who does so sooner is selfish or abnormal.

In this use, if you're not average, then you're a bad person.

This takes the statistical average which means most common, and warps it so that most common comes to mean normal (appropriate), and normal to mean how things should be and what people should do.

The statistical construct of average somehow becomes a moral guidepost.

The 'average person' as the ultimate flexible moral reference

The 'average person' is talked about often, but you will never hear someone say, 'As an average person, I think…' That's because this person doesn't exist.

The mythological 'average person' is often used to stand in for a moral or subjective viewpoint about our 'social norms' (expectations again!) for how to behave, usually the standpoint of the person speaking: 'The average person doesn't want to see smut on TV'; 'The average person doesn't engage in politics'; 'The average person likes to eat meat'; 'The average person wants a white picket fence house in the suburbs'; 'The average person doesn't understand climate change'; 'The average person wants convenience more than worrying about privacy'.Referring to the 'average person' hides the human tendency to assume we are more just, more trustworthy, more moral than other people - more overrating ourselves. The 'average person' idea is very flexible, so it can accompany judgments both positive and negative.

The mythological 'average person' is a great cover for not examining one's own assumptions or considering the complexity and variety of humanity.

Average as normal is strange

|

| Source |

We borrow the concept of average from statistics, a concept that is based on the fact that we are all different, we are each unique, humans don't come in a 'standard issue.' We expect that human attributes, skills and behaviours will be spread across a range, a distribution ('normal' or not) across a graph. We do seem to like the idea of a midpoint of human abilities as a reference for ourselves.

But then, we warp the concept of average as some sort of objective point, and that means being normal. We hear the word average in news, school reports, chat shows, ABS data, self-help books, and we think normal in sense of being just like everyone else or mediocre. Or we hear the word average and take it as a moral guidepost - something that should happen or a 'social norm'.

So, for some, a fear of being average is the fear of being mediocre or the fear of mindlessly adhering to social norms. Funny, that sounds like people are afraid of being human.

In part 2, I will explore how the words average and normal are further shaped to mean typical, compliant, ordinary and unremarkable. And something we are really afraid of: being boring.

Footnotes

- Statistics uses a few methods to work out an average, but I'm using the one most people know about in every day talking along: the arithmetic mean. I’m ignoring the average determined through the median and mode. And for any stats people, I am aware I am simplifying the concepts, but I’m not really writing this for you.

- The development of normed tests or norm-referenced tests involves extensive research. Norms are statistics that describe how a specified population (e.g. Australian men over 70, Victorian students in Year 5, etc) performs on a test. Using a normal distribution curve (Bell Curve), ‘norming’ established the test scores at various points along the curve that indicate below, at and above average scores for the entire population. In this specific application, the jargon term ‘the norm’ does mean average for that population. Read more. Such tests require specialists interpretation and are used to guide specialists’ decisions in terms of making a diagnosis.

- The key word in this sentence is alone. Norm-referenced tests are useful in their place. However, determining whether an average score means development is normal, as in not abnormal, requires more than a single test score. When child development specialists and educators refer to ‘the norm’ as in the average, on child development tests, they are not making a diagnosis. They are tracking learning which is much more complex and complicated to track than something like lung capacity or bone development. So, the meaning of the test score depends on what is being tested and considering the enormous variability we expect to see in child development. I saw a lot of ‘faux diagnostic’ statements in my time working in early childhood, by people putting too much faith in single test results.

- This was based on my expertise in early childhood, not just blind optimism or pigheadedness.

- Brummelman, E., Thomaes, S., Nelemans, S. A., Orobio de Castro, B., & Bushman, B. J. (2015). My child is God’s gift to humanity: Development and validation of the Parental Overvaluation Scale (POS). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(4), 665–679

- Afraid of being average? Andy Orr https://www.flickr.com/photos/aorr/1229272894/ [CC BY-NC-ND]

- Calculating the mean, Benjamin Harrison https://slideplayer.com/slide/13247626/ [Public Domain]

- Normal distribution (altered by author to remove stats symbols), LibreTexts https://stats.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_Statistics/Book%3A_Introductory_Statistics_(Shafer_and_Zhang)/05%3A_Continuous_Random_Variables/5.02%3A_The_Standard_Normal_Distribution [CC BY-NC-SA]

- Karl Pearson quote, created by author from https://www.quora.com/Why-is-the-Normal-distribution-called-Normal and image from Statanalytica (no longer online)

- Lung capacity test, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH), via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spirometry_NIH.jpg [CC BY-SA]

- Dunning-Kruger effect, https://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/is-dunning-kruger-a-statistical-artifact/ [CC BY-NC-ND]

- Child doing test, Tamara Chilver http://www.teachingwithtlc.com/2007/09/help-my-child-is-not-grasping-concept.html [CC BY-NC-ND]

- Excellence and mediocrity, https://www.maxpixel.net/static/photo/640/Passably-Mediocre-Excellent-Reasonably-Directory-1274229.jpg [free images]

- Approval thumbs up for your behaviour, https://www.peoplematters.in/blog/watercooler/little-things-that-make-a-difference-feedback-3268 [CC BY-SA-NC]

- Dr Evil, ‘Normal’ https://makeameme.org/meme/normal-49va2l [used under terms]

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated. After you click Publish (bottom left), you will get a pop up for approval. You may also get a Blogger request to confirm your name to be displayed with your comment. I aim to reply within two days.